Ashutosh Potdar: How do you see the exhibition embodying the idea of ‘amphibian aesthetics’, the ability to move between multiple worlds, perspectives, and temporalities? In what ways has this idea shaped how you selected the works?

Riyas Komu: The curatorial strategy of ‘amphibian aesthetics’ works in several dimensions. Firstly, it asks who is the ‘artist’ today and how does one learn to artfully survive the present times. In responding to this question, our curatorial process brings together diverse disciplines in conversation with each other – from engineers to artists, space researchers to comic artists, poets to film makers and painters to architects within the space of the exhibition. Secondly, the works bypass binary imaginations like tradition/modernity, Oriental/Occidental, terrestrial/oceanic, colonial/post-colonial, Left/Right etc. in favour of inhabiting the entangled simultaneity of our times. Thirdly, these artworks exist not only within the space of the gallery, but also extend out onto the city walls, to the waters of Kochi, allowing the public to engage more closely with the ideas that artists bring for a closer consideration. Imagining the city as one’s site, the curatorial strategy fluidly works across mediums and materials in order to aesthetically reach out to people, to make them a little more curious about the world around them. We believe that we are in a space where we need to harness the knowledge from different disciplines to speak to different audiences. At the centre of the initiative is the understanding that people are repositories, protagonists, destinations, and custodians of the knowledge generated through these processes.

Ashutosh: You describe the amphibian aesthetic as a way of moving beyond binaries that no longer serve us. How does this idea function for you as a critical method of understanding the present moment, rather than simply as a theme, especially when thinking about the “terminal phase of human history” you mention?

Riyas: Firstly, binaries have become redundant at all levels, social, political, economic and philosophical; even in terms of the idea of the human. In the post-human, post-truth world we live in, we can’t afford to think and act in/with such binary concepts. Everything is mixed up, all boundaries are transgressed, and all hitherto solid systems are facing a meltdown. For instance, capital is freed from national boundaries and currencies; it has become mobile and fluid, and has changed into more abstract forms, while labour whose surplus produces it remains geographically scattered, internally fragmented and as a class, informalised. Covid pandemic was a biological moment when we realised humans are just one species among many, even as a single continuum of bodies on earth, contiguous and porous with the virus traversing through it seamlessly, and also through a viral network that links it with other species. Ecological issues and conflicts too can no longer be divided as local and global, or between the North and South, as the common destiny we share has now brought us face to face with the real possibility of extinction. Global politics too has outgrown its old binaries, like Communist/Capitalist, Democratic/Autocratic and so on; no either/or this/that categories work anymore. While digital media democratises information exchange it also provides State and Capital with monstrous powers of surveillance and control. So on and so forth in every area of life, polity, economy, ecology…

So any imagination, political or aesthetic, need to take this chaos – very structured at one end, and disastrously polymorphous at the other – into serious and urgent account. This is what prompts and provokes us to think about amphibian modes of understanding and expression, one that traverses across boundaries and binaries.

Ashutosh: Your curatorial note speaks about the need for rhizomic thinking to make sense of our entangled reality. How does this non-linear, interconnected way of approaching the world manifest in the physical layout of the exhibition: its layout, sequencing, and the relationships between the works?

Riyas: Each work in the exhibition triggers many interconnected stories and issues that can become ways to approach the contemporary. Works of Michalengelo Pistoletto speak of universal ideas of how every person is caged in their own societal construct in the bringing of his symbolic empty cage, or on the other hand how parts of the society have to reflect while being inside it through his broken mirror series. Pistoletto’s critical thoughts help frame the other works included in the exhibition that speak of specific stories of their place, that are felt as ripples in other regions through geopolitical currents.

Moreover, these artworks exist not only within the space of the gallery, but also extend out onto the city walls, to the waters of Kochi, allowing the public to engage more closely with the ideas that artists bring for a closer consideration. Imagining the city as one’s site, the curatorial strategy fluidly works across mediums and materials in order to aesthetically reach out to people, to make them a little more curious about the world around them.

Ashutosh: Drawing on Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, you refer to mushroom picking as a way of imagining ‘collaborative survival’. How does the exhibition move beyond depicting ecological crisis and instead use the works themselves to suggest possible strategies for survival in political, economic, or environmental terms?

Riyas: The works in the show in many ways, emerge from amphibian consciousness about contemporary world, lives and livelihoods; many of them tread the edges of seemingly contradictory fields and modes of existence, some probe at the subliminal ways of being and becoming, some explore ways in which collaborative survival and resistance erupts through the gaps and cracks of the present. What marks them is their encounters with uncertainties and ambiguities. For instance, T Ratheesh’s work looks at the complex ways by which our lives are ‘rooted’ in certain ideas and beliefs, and how transformations work their way through and around them. Appupen takes the sarcastic route to upset our notions about how power permeates the insides and outsides of our world, where being amphibian could also assume diabolical dimensions. Dima Srouji delves into the deadly art of survival in times like ours, where objects and sites take unpredictable forms and uses. Rami Farooq’s work again is about human resilience, not only against violence but also in the face of the indifference of the world. Other works like that of Shabnam Virmani and Shilpa Gupta explore the realm of music and song, to evoke forms of resistance by excavating spiritual and political histories of the sub-continent. White Balance puts together a body of work dealing with the amphibious nature of alphabets and language, silence and performance, memory and nightmares to re-image and reimagine our world as a plurality of difference, a multitude created through coexistence. These works resemble the mushrooms that remain hidden and unseen most of the time, but survive in the most desolate and difficult conditions, and sprout through the cracks and crannies towards sunlight and air.

Ashutosh: How does artists’ multidisciplinary practice, which brings together scientific information, observation, and speculative imagination, express the ‘web and weave of materialities and immaterialities’ that you see as central to an amphibian way of sensing the world?

Riyas: Artists who work across science, observation, and speculative imagination offer a particularly rich entry into what we describe as an amphibian sensibility—one that moves fluidly between material and immaterial registers. During our curatorial process, the work of the collective City As A Spaceship (CAAS) became a compelling example of this approach. Their practice investigates the reciprocities between Earth and outer space by situating themselves in remote, extreme environments, where human perception is stretched and ecological dependencies become unmistakably clear.

Through close observation—of micro-worlds beneath the ocean, of life-forms evolving in fragile habitats, of atmospheric patterns and extraterrestrial analogues—they generate visualisations that are at once scientifically informed and deeply phenomenological. Their speculative designs are not fantasies detached from reality but propositions that emerge from intense engagement with material conditions.

Ashutosh: How do the materials and architectural references in the work allow for an engagement with the layered histories of a place and the conditions of precarity that define its present?

Riyas: In the exhibition, Palestine-born artist Dima Srouji directs our attention to the material intelligence embedded in everyday architecture. Her focus on the bathtub—an object designed for comfort and ritual care—reveals how, in Gaza, domestic materials are forced into new architectural roles under conditions of extreme precarity. Built as reinforced vessels within the home, bathtubs become improvised shelters when no time exists to reach basements or fortified spaces. Their hardened structure momentarily absorbs impact, shielding bodies from shards, bullets, and collapsing debris. Srouji’s work exposes how the built environment is continuously reinterpreted for survival, and how even the smallest architectural elements carry latent capacities that emerge in crisis. Through this attention to materiality, she underscores the fragile threshold between domestic space and protective architecture, showing how homes themselves adapt—tragically and resourcefully—to withstand the violence imposed upon them.

One of the centre pieces of the exhibition is a life size section of a shiphull by Shanvin Sixtous that creates an architectural experience of the ship. In addition, as the part of the ship that is always submerged under the water, the ship hull also suggestively gestures the artworks around to occupy the stories of deep sea. The exhibition thus is layered with architectural references through its design elements and they lend meanings to different objects.

Ashutosh: How does the use of satire and the creation of a semi-human figure like Amfy help to question human-centred narratives and suggest forms of agency that stretch beyond the limits of human perception?

Riyas: Fiction is a powerful tool to communicate with audiences amidst an age of information sensitivity and censorship. Fiction often helps to hold the complexity of a situation while engaging with serious ideas playfully. Appupen’s work on the Frogman Amfy uses satire as a way to not only speak critically to power but its comic form is also able to draw audiences of different ages, especially children, to the intricacies of their own landscape, issues of the environment and ecological interdependence. Using simple graphic novel form, Appupen’s work teases people to think of amphibious species as those with a special agency, and morphs their characteristics within human life. The new fictitious character is unburdened by manners of morality, rules of religion, laws of land or compulsions of culture. It freely takes on different identities and approaches to authoritarianism, surveillance, socio-political realities and ecological distress with dark humour and pop culture treatments.

Ashutosh: Why did you choose the multi-channel video format to explore the life of a structure like a masjid, and what does this fluid and shifting mode of presentation reveal about the building’s relationship with its community and its environment?

Riyas: UAE based artist Rami Farook gathers more than two hundred vertical-format videos from public online sources, moving between destruction (of mosques razed in India, China, and Gaza); preservation (Cheraman Masjid in Kerala that is the oldest mosque in India and Masjid Quba, each upheld through centuries of devotion; and protection (most urgently at Al Aqsa, where guardianship unfolds in real time). Each video carries a pulse of its own while opening into the next, with sounds intersecting in an unsettled field. The multiplicity of its sources, the varied geographies in which it is viewers, their differing synchronicities and temporalities are exemplified in the installation of this work through multichannel format. It makes us realise the different relationships people have with spaces of worship across the world and how they are emerging in constantly transforming cultural and political geographies.

Ashutosh: Your curatorial note emphasizes the hydro-social concept: the idea that the social and the hydrological are inseparable. Beyond works that explicitly foreground water, how does this perspective shape the way you want audiences to ‘read’ a painting where water might appear only through atmosphere, climate, or the suggestion of sustenance?

Riyas: Our close engagement with Kerala’s history compelled us to consider the fluid exchange of ideas, resources and material through the waters, as against the terrestrial imaginations through which history is written. In Kochi, more than thirty communities have lived side by side within a mere three-square-kilometre stretch. Few cities in post-Independence India hold such a dense layering of coexistence. Kochi has long been a threshold space: a historic port shaped by Arab, Jewish, Portuguese, Dutch, and British encounters; a town where caste, trade, migration, and local resistance have continually redefined what it means to live together. One can see all these layers existing simultaneously in Kochi, in effect, a social life that became possible because of movement across its waters.

Audiences will encounter artworks in different mediums that hold these material and non-material ideas, where memories of water, community and vulnerability reside in different forms. We would like the viewers to recognise that when water is not visually present, it exists as humidity in a landscape or as the ecological rhythms that shape daily life. The works gathered here reveal these interrelationships in material and spiritual registers, drawing from pasts and projecting toward possible futures. They remind us that architecture, craft, ritual, and image-making in Kochi have always been shaped by the tides: by cycles of abundance and scarcity, by routes of arrival and dispersal, by the precarity and resilience of communities who have long depended on water as both sustenance and threat.

***

Ishara Art Foundation is presenting a group exhibition, “Amphibian Aesthetics” from 13 December 2025 to 31 March 2026 at The Ishara House, Kochi, Kerala.

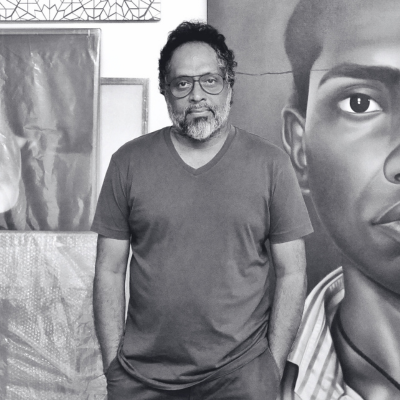

Image Courtesy: Ishara Art Foundation.

We are also thankful to Menaka Mahtab of Art Fervour.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram